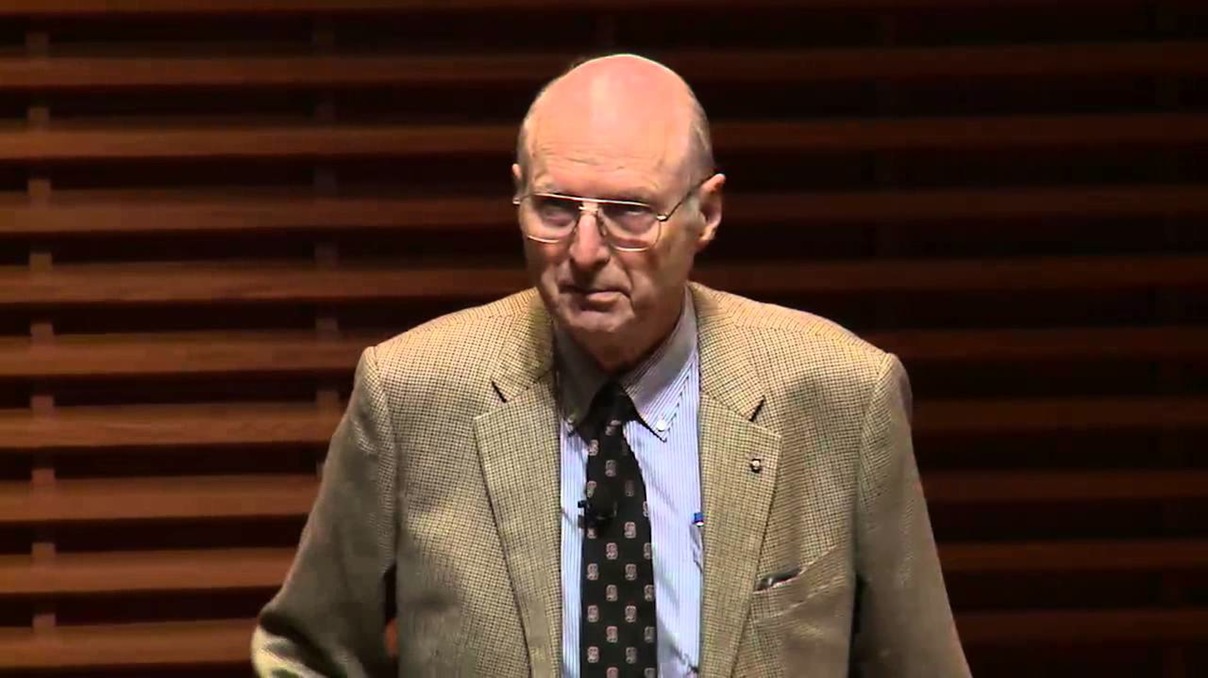

Alain Enthoven

TOWARDS A NEW ORDER

The most prominent theorist of the 'internal market' was the American, Alain Enthoven. Enthoven came to Britain in 1984 to examine the workings of the NHS at the invitation of the Nuffield Trust (at that time the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, originally established in 1939 with the innocent purpose of researching the problems of hospitals outside London). He gave his conclusions in a highly influential paper published by the Trust in 1985: Reflections on the Management of the National Health Service. It may be a little invidious to evoke Enthoven's career in military research at the time of the Vietnam War, prior to his developing an interest in health but the temptation is difficult to resist. This is from the account of his career on the Stanford University website:

'Professor Enthoven holds degrees in Economics from Stanford, Oxford, and MIT. He began his teaching career in 1955 while an Instructor in Economics at MIT. In 1956, he moved to the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica and participated in continuing studies on U.S. and NATO defense strategies. In 1960, he moved to the Department of Defense, where he held several positions leading to appointment, by President Johnson, to the position of Assistant Secretary of Defense for Systems Analysis in 1965. His work there is described in the book How Much is Enough?, coauthored with K. Wayne Smith and published by the RAND Corporation [the book is an insider account of policy making during the Vietnam war under Robert McNamara, 1961-8 - PB]. In 1963, he received the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service from John F.Kennedy. In 1969, he became vice president for Economic Planning for Litton Industries [major military equipment contractors - PB], and in 1971 he became president of Litton Medical Products ...

'He has been a consultant to the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program since 1973. He has served as Chairman of the Health Benefits Advisory Council for CalPERS, the California State employees’ medical and hospital care plans. He has been a director of the Jackson Hole Group, PCS, Caresoft Inc., eBenX, Inc. and Georgetown University.'

In a later paper by Enthoven published, again by the Nuffield Trust, in 1999 - In Pursuit of an improving NHS - he stresses the limitations of Clarke's reforms but he also expresses himself satisfied with the apparent direction of travel and especially with the continuation of that direction of travel by New Labour, despite its manifesto pledges. He is quite savage in his critique of the NHS as he found it in the 1980s:

'When I came to study the NHS in the 1980s, I encountered a gridlock of perverse bureaucratic incentives. People found that the best way to strengthen their case for more resources was by doing a poor job with what they had. If they were efficient, they would be forced to subsidise the inefficient. They also knew that if they improved the quality of their services, they would attract more patients but not the additional resources to care for them. In other words, "No good deed goes unpunished." The best course for one’s career was to please the people in the hierarchy who control one’s budget and career, rather than innovating to make things better for patients. The predominant ethos was to "play it safe, don’t make waves, don’t risk being seen as hard to get along with, and above all, don’t challenge poor performers." By contrast, the incentives for providers in competitive markets generally are to improve the product or service; reduce the cost of producing it; and produce it in just the right amount.'

Clarke's reforms were an improvement:

'The internal market in the NHS was an attempt to introduce some market incentives into a centrally planned, hierarchical system while maintaining universal and free access to health services. It recast the health authorities as purchasers of services on behalf of people in their districts, rather than as higher-level service delivery managers. Each district was to secure the best, most cost-effective services it could for its patients, whether or not those services were provided by the district’s own hospitals. The internal market funded districts on the basis of needs-based capitation rather than historical patterns of resource use. It encouraged hospitals to become separate, self-governing legal entities that would earn revenues from health authorities by providing services to area residents. It encouraged general practitioner (GP) practices that would be large enough to accept responsibility for managing an expanded capitation payment for a range of services beyond primary care, including outpatient services and elective surgery. GPs became resource managers.'

But he is dissatisfied. In particular:

'reliable quality-related information is virtually nonexistent in the NHS. Many people appear afraid of it. Before reform there were no systematic reliable data on the costs of services ... [E]ven today what data are available are quite inadequate. For example, the 1998 NHS Reference Costs cover only about 40 percent of inpatient hospital costs ...

'Authorities also lacked freedom to buy selectively. They often were constrained in attempts to change their source of supply. Market discipline requires that some ineffective providers be allowed to fail. However, no hospitals were allowed to do so ...

'In the end, instead of "money following patients," as Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher had proposed, patients followed money. That is, they went to where their health authority had contracted ... But unless patients can freely change providers, a conflict with equity exists. People who reside in areas served by inefficient hospitals get fewer services than do those living in areas served by efficient hospitals. The principle of fairness suggests that the inefficient hospitals should be paid more money so that their patients are not disadvantaged by the hospital’s inefficiency. But this would reward hospitals for their inefficiency. If patients could switch hospitals, they could move to efficient ones and leave the inefficient to lose business and suffer the consequences. If patients cannot switch, it is difficult to reform incentives for efficiency ...'

In 1997, Labour came to power promising to end the purchaser/provider split and GP fundholding which they had been denouncing vigorously throughout the 1990s, and, with Frank Dobson as Secretary for Health, it seemed as if the promise would be fulfilled. But Dobson was replaced in October 1999 by Alan Milburn and, already in his November 1999 paper, Enthoven could see which way the wind was blowing:

'I find it noteworthy that despite its rhetoric about abolition of the internal market, the New Labour government has preserved its main components: the purchaser/provider split; the trust hospitals; and commissioning of secondary care services by GPs, with primary care groups (PCGs) and primary care trusts (PCTs) for all GPs replacing GP fundholding by some GPs. PCTs, with an average of 50 GPs and 100,000 patients, will serve all patients in their assigned areas and hold the full health services budgets for their patients ... The White Paper, The New NHS, makes it quite clear that PCTs will commission [ie buy - PB] services. PCTs are an extension of the fundholding and Total Purchasing Pilot (TPP) projects of the Thatcher government. This might actually be more effective and overcome some of the weaknesses in the health-authority-as-commissioner [ie purchaser - PB] model. So what exists in today’s NHS is an internal market model in a somewhat different configuration. It remains to be seen whether it will be allowed to work'

Which brings us back to the first article in this series, the summary of the book by Colin Leys and Stewart Player, The Plot against the NHS ...