Back to Robert Owen Index

Previous

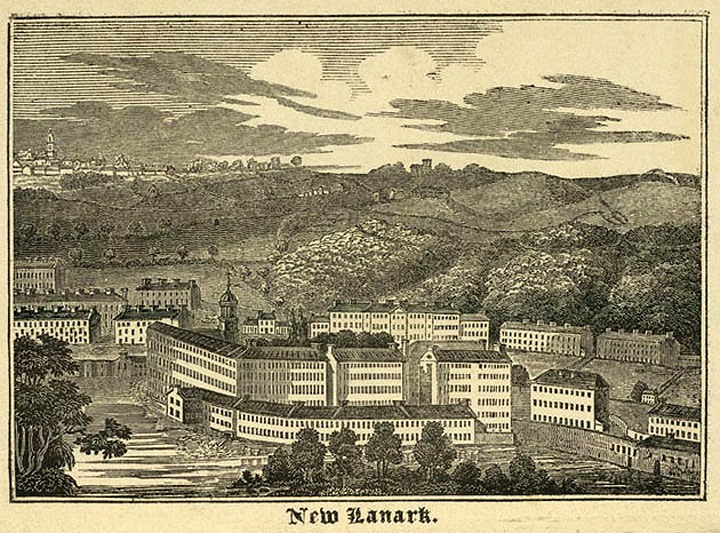

New Lanark in 1799

OWEN'S FIRST PERIOD OF REFORM

Owen describes the hostility and suspicion he himself encountered. He describes his work as a steady, patient encroachment on the vices of the workforce:

'Theft and the receipt of stolen goods was their trade, idleness and drunkenness their habit, falsehood and deception their garb, dissensions, civil and religious, their daily practice; they united only in a zealous systematic opposition to their employers.'

He emphasises that he never used punishment, that everything was done by patient and careful explanation, proving that better conduct led to greater happiness. As for the children:

'The system of receiving apprentices from public charities was abolished; permanent settlers with large families were encouraged, and comfortable houses were built for their accommodation.

'The practice of employing children in the mills, of six, seven and eight years of age, was discontinued, and their parents advised to allow them to acquire health and education until they were ten, years old. (It may be remarked, that even this age is too early to keep them at constant employment in manufactories, from six in the morning to seven in the evening. Far better would it be for the children, their parents, and for society, that the first should not commence employment until they attain the age of twelve, when their education might be finished, and their bodies would be more competent to undergo the fatigue and exertions required of them. When parents can be trained to afford this additional time to their children without inconvenience, they will, of course, adopt the practice now recommended.)

'The children were taught reading, writing, and arithmetic, during five years, that is, from five to ten, in the village school, without expense to their parents. All the modern improvements in education have been adopted, or are in process of adoption. (To avoid the inconveniences which must ever arise from the introduction of a particular creed into a school, the children are taught to read in such books as inculcate those precepts of the Christian religion, which are common to all denominations.) They may therefore be taught and well-trained before they engage in any regular employment. Another important consideration is, that all their instruction is rendered a pleasure and delight to them; they are much more anxious for the hour of school-time to arrive than to end; they therefore make a rapid progress.'

While all this was being done:

'Their houses were rendered more comfortable, their streets were improved, the best provisions were purchased, and sold to them at low rates, yet covering the original expense, and under such regulations as taught them how to proportion their expenditure to their income. Fuel and clothes were obtained for them in the same manner; and no advantage was attempted to be taken of them, or means used to deceive them.'

The end result was that:

'Those employed became industrious, temperate, healthy, faithful to their employers, and kind to each other, while the proprietors were deriving services from their attachment, almost without inspection, far beyond those which could be obtained by any other means than those of mutual confidence and kindness.'

CONFLICT WITH THE PROPRIETORS

Owen did not have full control over New Lanark. He had bought it with a group of proprietors who were first and foremost interested in it as a business investment. They were not averse to Owen's improvements so long as the business continued to yield a generous return, which it did, but by 1809 they seem to have felt he was getting too ambitious. Owen offered to buy the enterprise from them but to do this he had to enter into a new partnership. The 'New Lanark Company' was formed with himself as salaried manager and largest shareholder. The same problems, however, arose, with the new managers complaining against the extravagance of Owens' plan for the education of children under ten who were not actually in employment. Owen prepared 'A Statement regarding the New Lanark Establishment' to explain his intentions. It included the essay on what he had done that was later published in the New View of Society. On the strength of this he managed to put together a group of wealthy and influential supporters who, in 1813, attended the auction and bought the enterprise. They included the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham but also a group of Quakers, among them William Allen who would later turn out to be Owen's nemesis.

Owen describes how after the auction he and his fellow proprietors drove to New Lanark. As they approached Old Lanark, they suddenly found themselves surrounded by an excited crowd which busied itself with unhitching their horses. The little group of philanthropists was alarmed. Owen himself was alarmed since he did not recognise many of the faces that were surrounding them. It turned out that these were the citizens of Old Lanark who wanted to welcome their visitors by pulling the carriage to their own town where it would be taken over for the rest of the journey by the citizens of New Lanark.

Though perhaps 'citizens' is not the right word since it implies the possession of legal rights and a degree of self government and, however well treated the people of New Lanark were, their relations with Owen were legally closer to the relation of subjects to an - in this case benevolent - master.

THE INSTITUTION FOR THE FORMATION OF CHARACTER

Owen was now free, or so it seemed, to develop his policy as he saw fit. He started work on a new building which was completed by the end of 1815 and opened at the beginning of 1816 under the name of the Institution for the Formation of Character.

The building had three large rooms, two on the upper floor, one on the ground floor. The ground floor was for infants, the two upperfloor rooms for older pupils. One of the rooms was laid out as a classroom on the conventional model, with desks and forms; the other was full of objects, pictures and maps, and was an open space which could also be used for singing and dancing. Instruction was free, though there was a nominal fee of 3d a month for the day school. The Institution was open to all in the neighbourhood, not just the children of the mills. There were no punishments or rewards: 'these children should never hear from their teacher an angry word, or see a cross or threatening expression of countenance.' There were no toys: 'thirty or fifty infants, when left to themselves, will always amuse each other without any childish toys.'

Music and dancing were taught, as well as military drill, since Owen argued that a society able to defend itself would have no room for a standing army. The children were given tunics designed to allow the free movement of the body - boys wore kilts, not trousers. During the Summer, there were excursions organised in the surrounding countryside, where Owen had arranged for paths to be laid out.

One group of visitors left a description of a little presentation given by the children:

'In another large room, six boys entered in Highland costume, playing a quick march on the fife, with all the boys and all the girls following in order, the rear being closed with other six boy-fifers. The whole body, on entering, formed a square : then, after practising right face and left face, they marched round the room in slow and in quick time. At the word of command, fifty boys and girls, by means of a sort of dancing run, met in two lines in the centre of the square ; and sang, with the accompaniment of a clarionet, When first this humble roof I knew, The Birks of Aberfeldy, Ye Banks and Braes of Bonny Doon, and Auld Lang Syne. The square having been re-formed at the word of command, other children came to the centre, and went through several dances in an elegant style. In England there would be great awkwardness in such a case, from the clumsy, or ragged, shoes ; but these youngsters went barefoot. The narrator describes the whole scene as most exhilarating, and as bringing tears to his eyes.' (Sargent p.204)

In 1817 during a tour of Europe Owen visited the schools of Johann Pestalozzi in Switzerland, Johann Oberlin, a Protestant pastor in Alsace, and Philipp Emmanuel von Fellenberg, who had established an agricultural college in Hofwyl. He was particularly impressed with Fellenberg where he later sent his own sons, Robert Dale and William. Owen may already have known about Fellenberg from an article published in 1813 in the Philanthropist, run by his partner at New Lanark, the Quaker, William Allen.